In this monthly column, George Miller, TUJ’s Associate Dean for Academic Affairs (ADAA), shares what’s going on at Temple University, Japan Campus (TUJ) and with his life in Tokyo. For this edition, he writes about visiting the imperial palace to see the first public appearances by the new emperor and running into owls, our graduates.

We parked our bikes at Hibiya Park and crossed the street, walking toward the Imperial Palace. A police officer stopped us and said that the line to enter the grounds through the Kokyo Gaien national garden was full.

Try the Sakuradamon Gate, he suggested with a smile.

My wife and I knew that getting to see the new emperor on the first day of his public appearances would be difficult, which is why we arrived at 8:30 am. The dawn of a new era was bound to bring droves of fans of the monarchy and people interested in the historic event.

So, we walked down the road, across the foot bridge, through the Sakuradamon Gate and onto the palace grounds. We were escorted immediately to a security tent where they searched through bags. Neither of us were carrying anything so we cruised through the check point. Everything seemed to be going so smoothly. They even handed us small, paper Japanese flags. Maybe we’d get to see the first royal appearance, at 10 am?

But then, we just stood there.

I didn’t have a specific reason for seeing the new emperor. I’m not a fan of the monarchy. I don’t revere them just because of their lineage. No one deserves respect simply because they were born to the right family at the right time. Nor does anyone deserve to be treated differently just because of their title.

But as a longtime journalist, I’m used to being at important events, seeing things as they happen. I don’t like my information to be processed through the lenses of other people when I have the opportunity to experience things myself.

And here I was, a half-Japanese person living in Tokyo during that rare moment, when an emperor abdicates and is succeeded by his son.

We waited in that narrow space between the two check points for about an hour. I started worrying about all the coffee I drank before we left home. And as the sun rose higher in the sky, I began to regret wearing jeans rather than shorts.

People around us stood motionless, and mostly silent. I’d guess that about 97 percent of the people were Japanese. Older folks started squatting and a few pulled their jackets over their heads to protect themselves from the now blazing sun.

And then the police officers called us to the second check point. Some people rushed to the security tent, as though that would get them to see the emperor quicker. Police officers waved metal detectors over us and then we hustled down a long, roped-off area, a cattle chute surrounded by thousands upon thousands of other people stoically standing in line.

And there we waited and waited as the sun burst in and out of the clouds.

As I stood there sweating, I wondered, “What exactly is the role of the emperor?” What does it mean to be the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people in the 21st century?

Emperor Showa, known as Hirohito while alive, had been considered a living god until Japan’s defeat in World War II. After the war, he became a steady but distant leader.

Emperor Akihito, who succeeded his father, seemed to take a friendlier approach, meeting with survivors of tragedies. Akihito and Empress Michiko knelt down and communicated with everyday people in ways that could not have been imagined 100 years ago.

Akihito’s son, now Emperor Naruhito, visited Australia as a teenager and was educated at Oxford, as was his wife, Empress Masako. They seem to be relatively modern people, so it’s exciting to think of what they will do in their positions. Will they encourage the nation to further globalize, maybe diversify the population? And will they champion the role of women in society in Japan?

After about 90 minutes of not moving at all, the police officers told the people in my column it was our turn to march across the stone bridge and enter the walls of the palace.

I gave a loud, “Woo hoo!”

I was the only one to make a noise.

Even then, the line was slow moving as we hit the bottleneck of the main gate. We crossed the iron bridge, Seimon Tetsubashi, and found ourselves on the grounds in front of the Imperial Palace reception hall.

I was dehydrated, tired and crabby – standing shoulder-to-shoulder with a gazillion strangers for three hours will do that to you. But it was thrilling to be in the crowd, surrounded by tens of thousands of people, many waving flags, all really excited.

Over the next 45 minutes, people entered the grounds and the crowd became more and more packed, like the Denentoshi Line during rush hour.

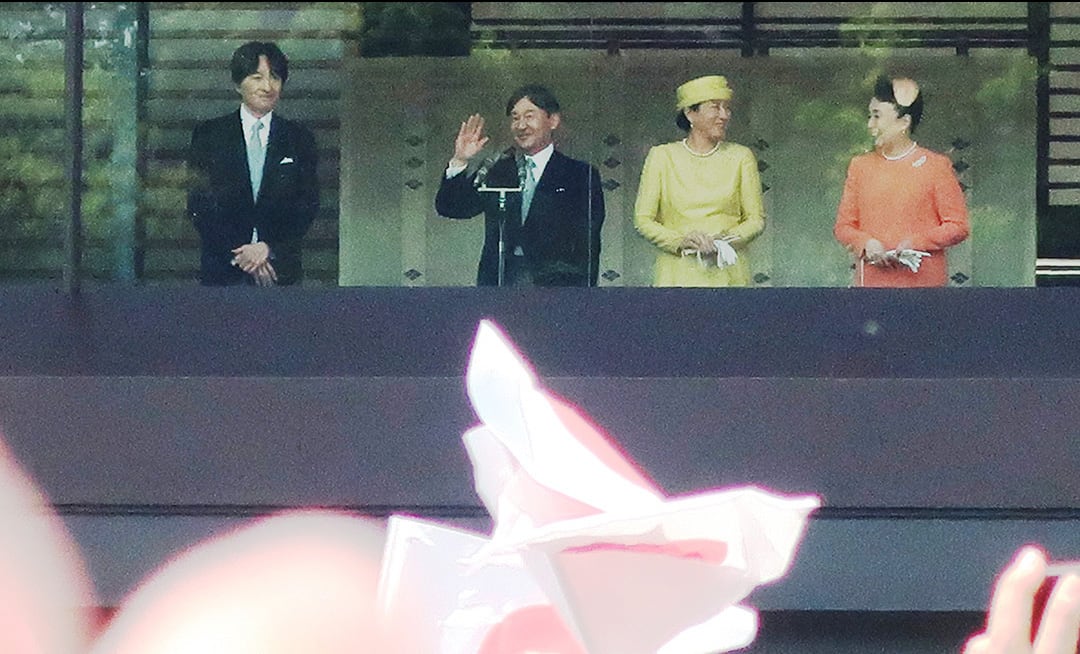

At noon, the new emperor walked out to the microphone and smiled at the crowd. He was joined by a royal court, which included 8 women in a rainbow of pastel dresses and matching hats.

The crowd went wild, waving their paper flags in the air. The emperor spoke briefly and then the court waved to the crowd.

It was over in a matter of minutes.

Many people kept waving their flags for a few more minutes and a handful of energized people yelled, “Banzai! Banzai! Banzai!”

It took about 30 minutes to exit the grounds and get away from the hoard of people. As we walked through the garden, a woman stopped me and my wife and asked if she could interview us for Asahi TV. We talked for a few minutes and when we finished, I handed her my business card.

“Oh, I went to TUJ,” she said. “And I studied for one semester on Main Campus in Philadelphia.”

It was a fine ending to an interesting morning.

I’m glad we experienced the emotions of the day. I will tell people about it for a long time.

Oh, and we’re famous in Japan now. We appeared on the “Saturday Station” program that night on television.